The Science Behind The Sinclair Method

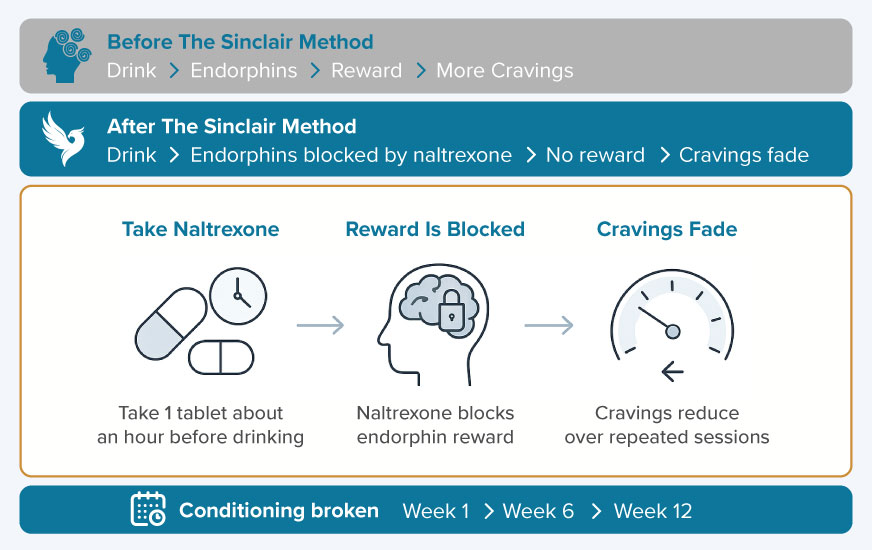

When you drink alcohol, your brain releases endorphins that activate opioid receptors. This then creates a rewarding effect, which over time conditions the brain to associate alcohol with pleasure.The more this reward pathway is reinforced through drinking, the stronger the cravings become and the harder it is to quit or cut back.

When you take naltrexone before drinking, it blocks the endorphin reward.Because the brain no longer receives the same reinforcement, the learned behaviour gradually weakens.

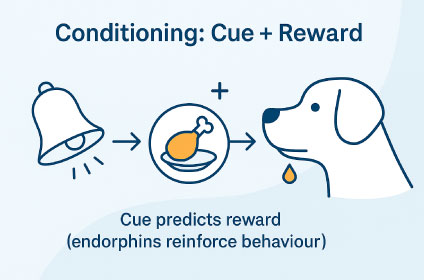

This follows the same learning principle shown in Pavlov’s experiments: when a cue stops producing a reward, the conditioned response fades.

On The Sinclair Method:

- The cue = drinking alcohol

- The missing reward = the endorphin release

- The fading response = craving and compulsive drinking

Over time, this process is called pharmacological extinction — the brain “unlearns” the addictive pathway.

The Alcohol Deprivation Effect

Why cravings can get louder when you try to stop

If you take a break from alcohol and your cravings get stronger, you are not weak. Your brain is doing something common. It has a name. The Alcohol Deprivation Effect.

What you might notice:

- You stop drinking for a while

- You expect it to get easier

- But urges can feel bigger the longer you go without alcohol

- Alcohol can take up more space in your head

Why it happens (simple)

When you drink often, your brain learns: alcohol = reward.

When you stop suddenly, your brain feels deprived of a reward it still expects.

And the longer you go without alcohol, your brain may still be wired the old way, so it keeps sending strong “wanting” signals.

To change that wiring, the brain has to learn a new lesson: alcohol does not deliver the same reward anymore. That unlearning is called extinction.

Pharmacological extinction is when the reward is blocked during drinking sessions, so over time the brain can weaken the link between alcohol and craving.

The key takeaway

Taking alcohol away can make the brain want it more for a while.

The brain needs time and the right method to re-learn

What helps

A plan that:

- Gives you clear steps each week

- Helps you handle cravings when they spike

- Supports consistency without willpower battles

How we support you

Our 12-week guided programme gives you a simple roadmap and expert support, so you know what to do next and you are not guessing.

What To Expect On The Sinclair Method

Weeks 1–2

You learn the routine: take naltrexone before

drinking, track units, notice first shifts in

reward after drinks.

Weeks 3–6

Cravings begin to reduce. Many

report fewer units, more control and less urge to continue

once they start.

Weeks 7–12+

Reinforcement weakened, drinking declines

further, some choose abstinence, many

maintain moderation.

The Pavlov Analogy

In Pavlov’s experiments, when the bell no longer predicted food, the dogs

stopped salivating. On TSM, when alcohol no longer delivers its endorphin

reward, the brain’s conditioned response — craving — fades

in the same way.

How The Sinclair Method Works

The Sinclair Method (TSM) uses a prescribed dose of

naltrexone taken about an hour before you drink. Naltrexone

temporarily blocks the brain’s opioid receptors, so alcohol

produces little to no endorphin “reward.” Without that chemical reward, the

brain starts to unlearn the link between alcohol and

pleasure. This learning process is called pharmacological

extinction.

Why The Sinclair Method Is Different

TSM

Evidence‑based alcohol

reduction. No forced abstinence. Blocks reward,

so cravings reduce and control returns.

Abstinence‑only

Stop immediately. Higher relapse risk for many.

Progress depends on willpower without medical blocking.

Willpower‑only

No medical support. Often leads to cycles of

restriction, lapse, guilt, repeat.

Information on this page is educational and not a substitute for medical

advice. Always follow your clinician’s guidance.

MEDICALLY

PROVEN RESULTS

MEDICALLY

PROVEN RESULTS